Why Myanmar is losing the Rakhine war

(Arakan Army’s insurgency has escalated into an open-ended military quagmire of rising social, economic and political costs)

By Anthony Davis, Yangon

The escalating conflict in Myanmar’s western Rakhine state has been tightly quarantined from news coverage and remained well below the radar of the international community since insurgent violence erupted in the New Year.

But two recent events that broke through the media firewall – an unprecedented government-imposed internet blackout and a rebel rocket attack on the outskirts of the state capital, Sittwe — have thrown the security crisis into stark relief while raising a wider question: Is Rakhine becoming “Myanmar’s Vietnam?”

On the face of it, comparisons between the insurgency in Myanmar’s western seaboard state and the war into which United States’ forces floundered disastrously in the second half of the 1960s and early 1970’s would seem improbable. No foreign forces are involved in Rakhine, one among several ethnically-driven armed conflicts in Myanmar; and the scale of fighting is hardly on a par with the far larger and bloodier war in Vietnam.

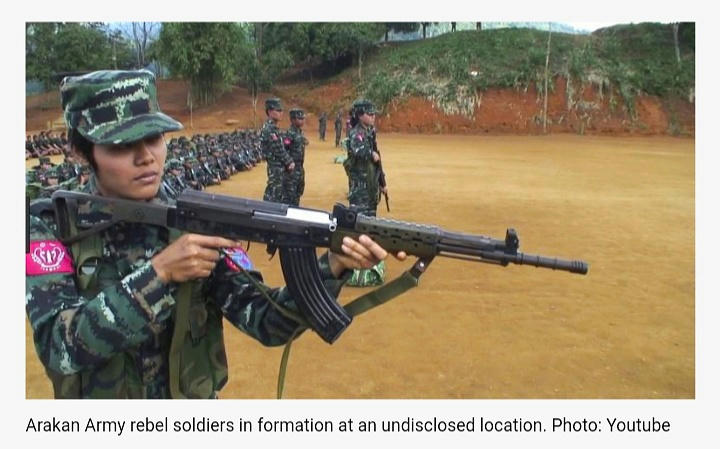

Nevertheless, the conflict between Myanmar’s armed forces, or Tatmadaw, and the Rakhine nationalist Arakan Army (AA) – a well-trained and equipped guerrilla force which enjoys sweeping popular support and is already inflicting serious casualties — is looking increasingly less like the military’s on-again off-again campaigns against other, older ethnic armed groups in remote border regions of the north and east.

Albeit in a far smaller battle-space, Myanmar’s Rakhine war is emerging as an open-ended military quagmire with social, economic and political repercussions from which the national mainstream will be lucky to remain insulated. Whether, like America’s war in Vietnam, it acts as a catalyst for wider social and political change remains to be seen.

Served by the Ministry of Transport and Communications on all four of Myanmar’s mobile service providers, the abrupt June 21 directive to shut down of all internet services in north Rakhine reflected growing government and military concern over the escalation of the conflict.

Despite widespread push-back from human rights organizations — including United Nations special rapporteur on human rights in Myanmar, Yanghee Lee — government officials have justified the blackout as a move to curb virulent online hate speech that has purportedly further alienated the local Rakhine population from Myanmar’s dominant ethnic Bamar community.

It remains unclear how much of the ethno-racial incitement has been driven directly by the AA – a group with various front organizations renowned for slick propaganda and social media savvy – and how much has been spontaneously generated by stepped up counterinsurgency operations and the excesses which invariably accompany them. The reality is almost certainly a mix of the two.

At the same time, however, there is little doubt that the internet shutdown was also likely driven by issues of military security and the use of encrypted messaging applications as intelligence and operational tools for the rebel forces and their widespread local support base.

Either way, the result is an information black hole beyond either mainstream or social media reporting and in which the worst instincts of Tatmadaw combat units now enjoy free rein.

The Sittwe rocket attack unfolded in the early hours of June 22 involving AA fighters firing at least three Chinese-produced 107mm surface-to-surface rockets at a military jetty on the Kaladan River some six kilometers from the city center. One hit a navy vessel killing two personnel and wounding a third.

Sittwe was last targeted in a coordinated wave of three improvised explosive devices (IED) blasts in February last year. Left outside government offices and timed to explode around 4:30 am, the devices were clearly not intended to cause casualties. With heavy munitions hitting a military logistics facility, the latest attack was of a different order and demonstrated a new AA capability to operate freely near the edge of the state capital.

It also established that the rebels have access to 107mm rockets. Likely purchased from the United Wa State Army (UWSA) in northeastern Myanmar, the country’s best armed insurgent outfit, the missiles have also been used by the AA’s ethnic Kachin, Kokang and Ta’ang allies, albeit far less effectively.

Often inaccurate free-flight projectiles with a range of up to eight kilometers, they are typically used for stand-off attacks on area targets and fired – as at Sittwe – in salvoes. Photographs suggest the AA launched the rockets across the wide river mouth from a distance of two or three kilometers.

As the monsoon season approaches, the Sittwe attack served to underscore the marked escalation of the conflict during the first half of the year. Since early January, when AA forces overran four police stations near the Bangladesh border in Buthidaung and put the insurgency squarely on the national map, hostilities have unfolded in three broad phases.

In January and February, the Tatmadaw, directed by de facto leader Aung San Suu Kyi’s civilian government to “crush” the AA, scrambled to beef up forces already based in the state.

An estimated 8,000 to 10,000 fresh troops were air-lifted and trucked into Rakhine and adjoining areas of Chin state, most of them elements of various mobile, centrally commanded Light Infantry Divisions (LIDs).

Even as new units arrived, the military launched a piecemeal counteroffensive centered on Buthidaung and Rathedaung where the AA – estimated to field a total of around 6,000 trained combatants — was clearly already well-entrenched.

Spilling into neighboring Ponnagyun and Kyauktaw townships, the drive was aimed at breaking up rebel concentrations as well as rooting out AA camps, training facilities and arms caches in mountainous and jungle areas bordering on the more densely populated plains.

At the same time, the army established new garrisons and artillery fire bases close to urban centers tasked with dominating the surrounding countryside and supporting infantry operations.

Tested in fighting in the northeastern Kokang region in 2015, the anchoring of sweeps on fire-bases is eerily reminiscent of American tactics in Vietnam. In Rakhine as in Vietnam, heavy artillery attacks have frequently taken the form of harassment and interdiction (H&I) fire — routine, largely random shelling intended to keep an unseen enemy off-balance — but which often hits villages and civilians.

A second phase of hostilities unfolded through March and April and saw the AA regain the initiative with some notably aggressive attacks across the flatlands of northern Rakhine.

Suggesting that earlier Tatmadaw search-and-destroy sweeps had been unsuccessful, some of these operations involved major ambushes of convoys on the national highway between Yangon and Sittwe; others saw hundreds of rebels launch frontal assaults on fixed positions.

On March 9, an AA attack on a police base on the national highway in Ponnagyun township killed nine officers. It came amid sustained clashes on the border separating Ponnagyun from Kyauktaw, during which AA envelopment of Tatmadaw reinforcements saw army commanders calling in close air support from new Russian Yak-130 ground attack jets.

The same day as the police base attack, AA forces overran an army tactical operations headquarters in Buthidaung near the border with Bangladesh, reportedly wiping out most of the garrison.

Among the hardest hitting highway ambushes was an attack on March 18 on an army convoy near the Mahamuni temple in Kyauktaw. An evidently close-quarter attack using small-arms and rocket propelled grenades (RPGs) left around 20 soldiers dead, according to local villagers.

The ambush also provoked a remarkable incident later the same evening when enraged army troops drove into the ancient Rakhine capital of Mrauk-U, an important tourist center, and opened random fire on buildings and civilians, wounding at least six.

The incident was publicized in courageous reporting by a journalist with Myanmar’s The Irrawaddy news site present at the scene. The military later asserted that AA fighters had infiltrated the town, a claim denied by the AA.

On April 9, the rebels maintained the pressure with coordinated assaults on a police compound which was being used as an army fire base in Mrauk-U and on another army base outside the town. Those attacks again left an estimated 20 government soldiers and police dead.

Between mid-April and June a third phase of hostilities saw fewer major AA operations as the military ratcheted up efforts to assert control over the plains and triggered multiple clashes.

Tentatively started in February, this process has relied on stepped-up raids on villages accompanied by widespread detention of men and youths suspected of association with the AA. In Kyauktaw, arrests of village headmen appointed by the government’s General Administration Department have reportedly triggered mass resignations from the post.

Amid escalating clashes and reports of military abuses, the number of civilian internally displaced persons (IDPs) has now reached around 40,000, with concentrations in Mrauk U, Kyauktaw and Ponnagyun townships.

Military casualties on both sides have risen steeply. The AA itself has claimed that between December 16, 2018 and June 8 this year it has inflicted slightly over 1,100 fatalities on the military in some 500 separate contacts, 237 of them protracted engagements lasting between half an hour and three days.

Dismissed by the Tatmadaw – which does not issue its own casualty statistics – the AA’s figure of over 1,000 killed is almost certainly inflated for propaganda value. However, one foreign intelligence official monitoring the conflict who spoke to Asia Times estimated that between January and May the army had suffered at least 400 deaths while AA losses had crossed the 100 mark.

The “body-bag factor” – the political impact of a rising toll of army dead on public opinion in heartland Myanmar – has yet to be felt at any significant level. No organized “peace movement” has emerged, and the absence of a military draft in Myanmar coupled with tight surveillance of student and civil society organizations makes such a development unlikely in the short term.

Just six months into the insurgency, however, the growing number of young field-level officers falling to AA snipers is a hard reality which has gained some attention on social media. Beyond the rising level of hostilities and human suffering, the Rakhine war poses threats that are unlike those in other theaters of conflict in Myanmar.

At one level, there is a significant ethnic Rakhine component within the ranks of the Tatmadaw, which poses obvious security risks as ethnic polarization grows. Indeed, some analysts have noted the salience of out-of-area LID battalions deployed in operations since January, an apparent reflection of high-level concern over the reliability of local army units which draw heavily on ethnic Rakhine recruits.

Remarkably, the deployments into the Rakhine theater since January have included five of the army’s 10 LIDs and elements of another three, an unprecedented and risky concentration of leading combat formations against a single insurgent enemy. As the fighting season got under way in December, the Tatmadaw sought to balance the risk by declaring a months-long unilateral ceasefire covering five insurgency-prone military regions in the north and northeast of the country.

At the same time, the AA’s core area of operations is close to both the prospective China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC) and its terminus at Kyaukphyu deep-sea port and to the cities of central Myanmar. Despite an IED incident in April involving a device left outside a government official’s house that was safely disarmed, to date there is no reason to suggest the AA has any interest in directly targeting CMEC-related installations.

That said, the group is clearly shifting its organizational center of gravity and operational focus out from under the wing of its ally and one-time mentor the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) and away from the KIA headquarters at Laiza on the Chinese border.

Significantly, that shift distances the AA from Chinese influence and pressure while its new proximity to the CMEC terminus gives it obvious leverage.

So, too, does a sympathetic diaspora of ethnic Rakhine factory labor in cities in central Myanmar, most notably the old capital of Yangon. If the rebels were to use Trojan Horse sympathizers to support IED attacks in urban centers in the country’s heartland, a capacity it has undoubtedly already developed, the implications for foreign investment and the economy would be grave.

Over decades of civil war, Myanmar’s multiple insurgent groups have avoided carrying their campaigns to major cities. Whether the AA, a new and determined force on the national stage, will be willing to play by the same unwritten rules is unclear.

What is not in doubt, however, is that the potential impact of a protracted conflict on the stability of Myanmar as a whole is real, and that few, if any, Tatmadaw commanders will likely have reflected on the lessons of another Southeast Asian war fought to disastrous effect some 50 years ago.

==========

Source: https://www.asiatimes.com/2019/07/article/why-myanmar-is-losing-the-rakhine-war